Carbon Copy Cats

Originally printed in Newsday on April 4, 2002

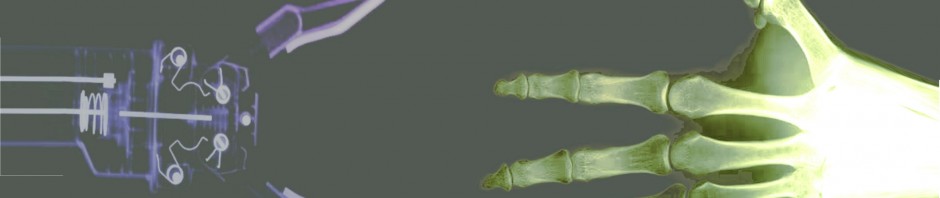

Born the way millions of other kittens were, her name revealed that something was different. They called the first cloned cat “cc”. Those letters on the end of a memo let us know the message has been sent forth. cc has broadcast her message. We have entered a new era.

Fear loosing a pet? Distraught over your beloved pet’s passing? The cc researchers, Genetic Savings & Clone Inc. of College Station, Texas, have the answer. Deposit your pet’s genes in this bank, freeze the assets for a couple of thousand dollars, and when the time is right (and you can spare $200,000), your investment will be cloned to maturity.

In an entrepreneurial system, this development was to be expected. To some degree, we already select and choose what we want in pets. We try one for a while. If it doesn’t work out, we try another. If it does work, we love the companionship. But cloning pets? It’s one thing to clone mice for research or farm animals for pharmaceuticals. But cloning pets for emotional comfort is new. It takes us one step closer to cloning ourselves.

If we move in this direction, we may treat our kids more like pets. Recent developments show the balance is swinging towards valuing offspring for their functional utility more than their inherent value. Couples select embryos based on the likelihood of producing cures for sick siblings. The goal is understandable. But the (perhaps) unintended message is that we can pick and choose the characteristics we want in our children. Cloning pets is the same. We don’t have to take our chances with the genetic lottery. We don’t have to rely on our training skills. We’ll clone the pet we want.

The problem here is visible in cc. She doesn’t have the same coat colorings as her clone. Animal’s markings are influenced by conditions in the womb, not just genetics. Behavior and personality are even more complicated. If we clone humans, the personality differences will likely be very significant. A clone of your loving grandmother could turn out to be a cruel criminal.

The pet cloners know this and make it clear they cannot resurrect identical pets. So then, why take the risks? cc was the one success out of 188 attempts, resulting in the deaths of many cloned embryos. The numbers with Dolly, the cloned sheep, were similarly discouraging. Now Dolly has arthritis at a very young age, in joints not usually affected in sheep. Cloned mice born in Japan have almost all died very young, apparently from liver problems. Yet the first statement in the Genetic Savings & Clone Code of Bioethics is that “no animals will be intentionally harmed at any point during this project, including the research phase” or be “subjected to risky procedures of any type.” The cc message should be that cloning is risky, not attractive.

The cute humor behind the name, Genetic Savings & Clone, may become very ironic. Many remember the pain of trusting Savings & Loan ventures that couldn’t deliver. We should be wary of placing our trust in biotech answers to life’s deeper issues. Death and disease are difficult. Cloning loved ones will not bring them back. Spot the Clone will not fill Spot’s paws any more than an unrelated dog. He may make Spot’s passing even harder by reminding us of how much he isn’t Spot.

Cloning pets is not needed. It uses resources that could better be used to care for existing animals and humans. If we accept cloning man’s best friend, we make it easier to accept cloning humans. This will subject untold numbers of humans, born and unborn, to the risks of cloning.

No child can replace a lost child. No clone will replace a loved one. Yet in grasping after straws we set ourselves up for further pain. We prolong our grief. And we run the risk of viewing humans as pets – creatures to be selected, bred and trained as we see fit. The price will be respect for human dignity.