Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise: Living Ethically in the Light of the Bible

John 6:41-59; 1 Peter 3:13-22; Ecclesiastes 12:1-8; Jeremiah 40-42

The book of Ecclesiastes begins its final chapter with one of its bleakest and most difficult passages. It calls our attention to aging, death and subsequent mourning. The author ends with the same refrain he began with: ‘“Meaningless! Meaningless!” says the Teacher. “Everything is meaningless”’ (v. 8). While the overall theme of aging and death is clear, many of the details are obscure and have been interpreted in various ways. The difficult of the passage lies in its complexity and many layers of meaning. Some take the passage literally, others symbolically, and others find allegorical meanings. Each proposal runs into problems as none of them accounts completely for all the images. The author may have done this deliberately, leaving readers unsettled in our inability to figure out ‘the answer.’ This fits with the overall message of Ecclesiastes: there is much that we do not know. At the same time, the ambiguity allows each of us to see aspects of our own experience in the imagery.

The literal, figurative and allegorical meanings in the passage are not mutually exclusive. The literal meaning focuses on the things, events and actions as described. The passage is often taken as a literal description of a funeral, with mourners on the street. As the procession passes through the community, some tremble and others become fearful. Some look out their windows, and doors are closed in respect. Work like grinding grain ceases and in the silence, only the birds are heard.

This is not just an impersonal description about a funeral. The second person used in verse 1 makes this personal: it is our own funeral we are to think about. In our youth and vigour, we are to remember that we will die some day. In western society we avoid thinking about aging or death, and do much to hide or deny its reality. Instead, Ecclesiastes encourages us when we are young to carefully reflect on our inevitable aging and death. By the end of the passage we will see why.

Some images do not fit well with an individual funeral, such as the darkening of the sun, moon and stars, and the degree of impending doom. These images lend themselves to symbolic interpretation, where a literal event simultaneously has a broader, figurative meaning. Many of the images here are common to prophetic warnings about divine judgement (like in Jeremiah 42). While the passage may remind us of our individual deaths, it can additionally remind us that all will die eventually, and a time of judgment is coming (11:9). We must also grapple with the terror and darkness of the end times.

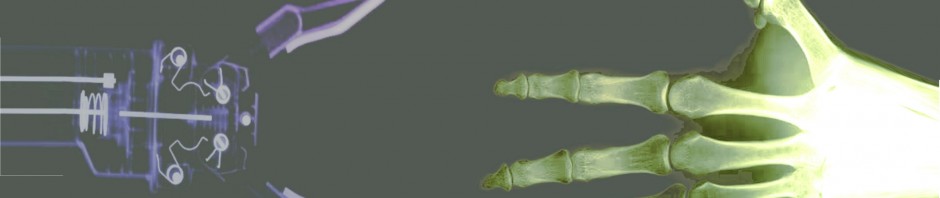

Allegorical meanings have been identified in traditional interpretations of the poem. For example, the ‘grinders’ are said to stand for someone’s teeth, which can become fewer as people age. Those looking through the windows are said to be eyes, which grow dim with aging. The almond tree blossoms may be hair greying. The overall allegory is thus about aging. However, disagreement exists over the meaning of most other terms in the passage. The ‘keepers of the house’ have been seen as arms or legs that tremble, but why interpret them this way? The ‘doors to the street’ have been seen as lips, but aging does not usually close the mouth. The problem with allegorical interpretation is that unless the author provides an interpretive key, or the connections are obvious, almost any meaning can be proposed.

The author may not have intended that the meaning of every phrase be clear and apparent. Overall, the literal, figurative and allegorical meanings together communicate a sense of fear and unease about aging and death. The author wants each of us to think about what lies ahead of us. While he concludes the poem with his repetition of ‘meaningless,’ this word (hebel) also means temporal or short-lived. As Paul says, our troubles are momentary (2 Corinthians 4:17). Aging and dying have many bad aspects, but we are not without hope. We should remember (a word that means reflect deeply on) our Creator (v. 1) and that death brings us to our eternal home (vv. 5, 7).

In Jesus Christ, we find the complete answer to death. The author of Ecclesiastes had some sense of eternal life, but a fully developed view had to await the resurrection of Jesus and his victory over death. Those who believe in him will live forever (John 6:47-49). We must still age and die, but we have eternal life with Christ. This gives us ultimate hope in the face of life’s trials and uncertainties, which we should be ready and able to explain to others (1 Peter 3:15). Focused on eternity, we do not lose hope, even though our bodies are wasting away (2 Corinthians 4:16-18). We should not despair over aging, nor clamour after every alleged elixir of youth. Neither should we give up on life and end it prematurely. Death may seem preferable, but like Paul we should chose life because this is better for those around us (Philippians 1:21-26) and allows us to continue to please God in our bodies (2 Corinthians 5:6-9). The message of Ecclesiastes is that we should enjoy the pleasures of life that God gives us and draw close to him as we pass through this temporal life to an eternal home with him.